Neo, 6 years and 600 citations later

I was excited to see that Neo, the neural query optimizer, got its 600th citation! It’s nice to have a quantification, but what I’m most proud of is the impact Neo had on the research community.

Neo was simultaneously the last paper of my PhD at Brandeis and the first paper of my postdoc at MIT. Working with my advisor Olga and then-1st-year-PhD student Chi at Brandeis, along with Mohammad, Hongzi, Pari, Nesime, and Tim (my future postdoc supervisor) at MIT, was a great experience. I couldn’t think of a better way to end a PhD, or to start a postdoc!

What is Neo?

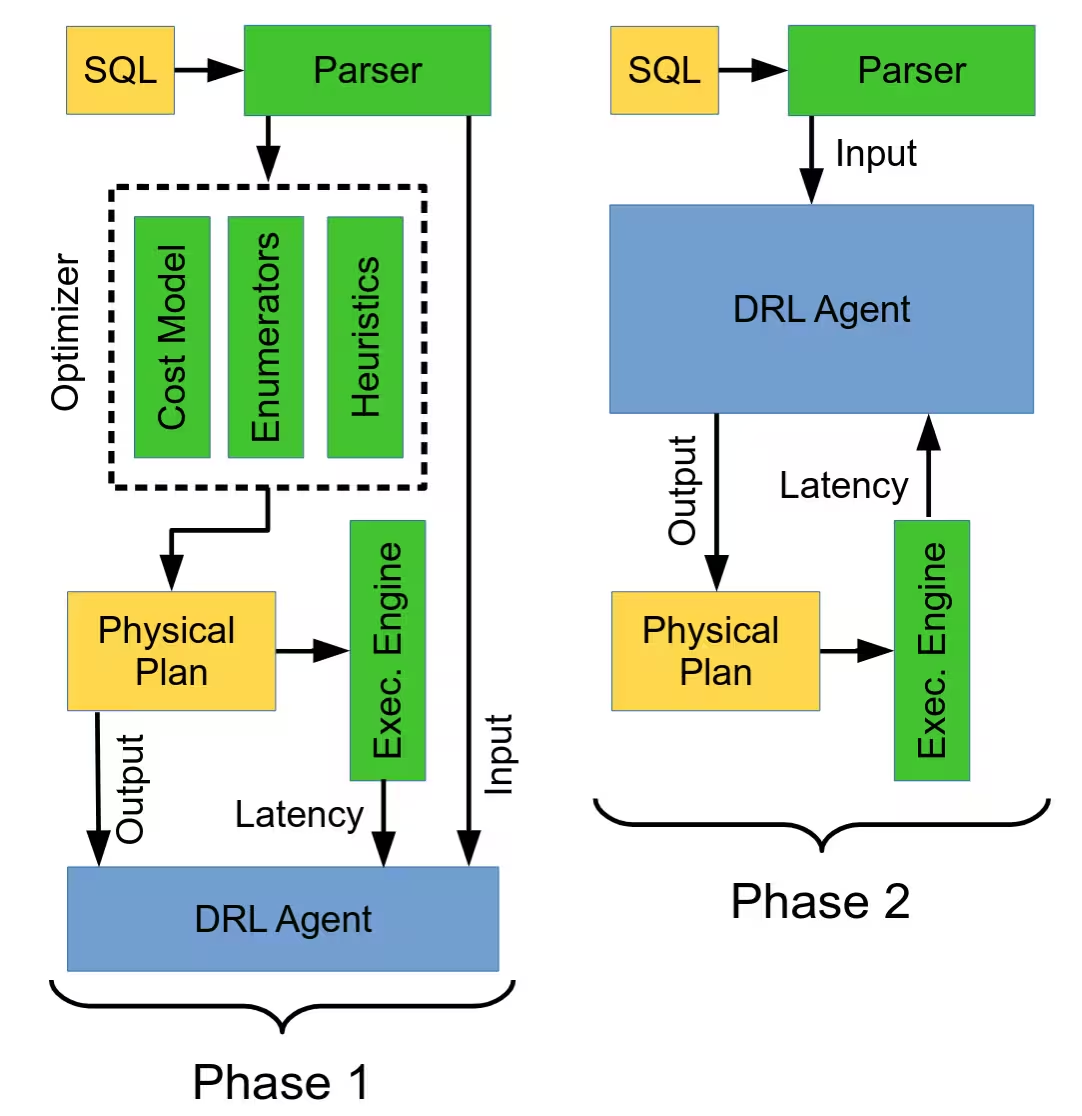

Learning a query optimizer with deep reinforcement learning is interesting because making a query optimizer is a long and complex task. Modern query optimizers, like the one found in SQL Server, represent decades of engineering effort. If one builds a new type of system, are they doomed to spend decades of engineering effort building a query optimizer as well? Or is there another way?

Neo showed that deep reinforcement learning, with a little bit of demonstration from a simple query optimizer, could eventually learn policies that matched the performance of state-of-the-art (in 2019) query optimizers. Neo thus represented a hope that query optimizers for future data systems could be “learned” instead of manually built.

How’d we get there?

Neo was the culmination of two prior works from my PhD investigating how deep reinforcement learning could be applied to query optimization. Initially, in ReJOIN, we showed that an off-the-shelf PPO algorithm could find plans with low costs according to the query optimizer’s cost model. Concurrently, a team at UW (Ortiz et al.) discovered that the state learned by a deep RL agent contained rich information about the query’s structure. A little later that year, a team from Cal (Krishnan et al.) showed how Q-learning could be used to optimize queries against a cost model.

In order to get from here to Neo, we needed to solve two key problems.

Key Problem 1: Sample Inefficiency

Deep reinforcement learning algorithms are notoriously sample inefficient. While RL models could learn to solve complex problems, they might need millions (or even trillions) of “episodes” in order to get there. This sample inefficiency is easy to get around in traditional RL areas like video games. If you are bad at Pacman, you’ll get eaten by a ghost quickly. This means you can get a lot of episodes per wall-clock hour.1 This is not the case in query optimization: if you pick a really bad query plan, it could take days to execute instead of seconds. In other words, in query optimization, doing worse takes longer.

Because of this, throwing an off-the-shelf RL algorithm at query optimization is not really viable. In our vision paper early the next year, we laid out three different potential ways to solve the problem. One of those ways – learning from expert demonstration – became Neo. Later, another idea, bootstrapping from a cost model, was explored by Berkeley in Balsa.

Key Problem 2: Inductive Bias

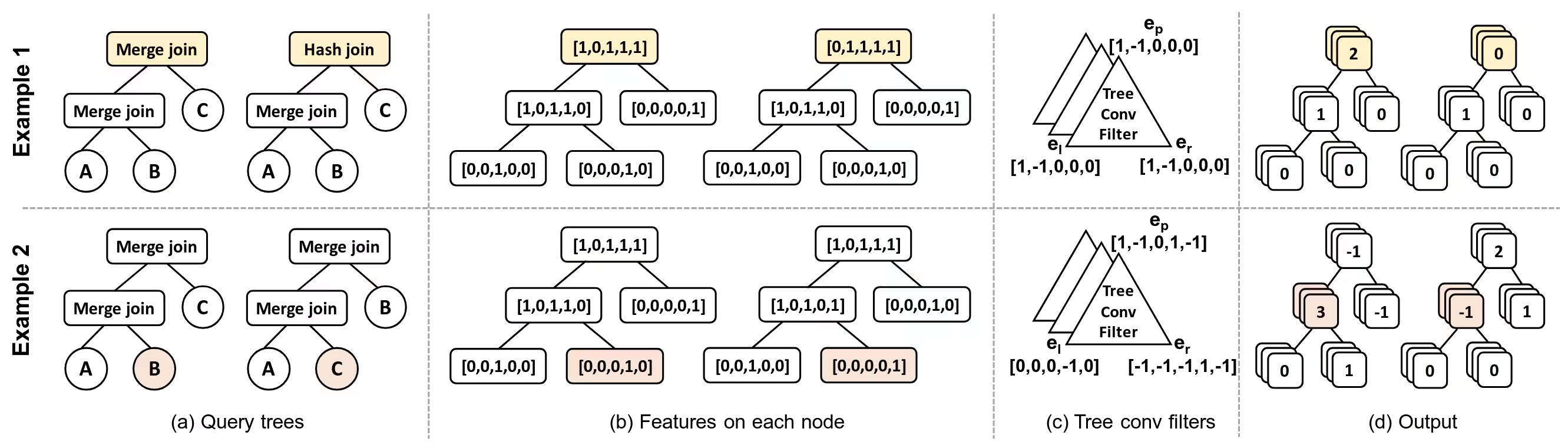

Half the battle of getting deep learning to work well is getting the right inductive bias. Throwing a fully connected network at a problem, while theoretically sufficient, is rarely the right choice. Think about the areas where deep learning has had the most success: in computer vision, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) excel at modeling low-level vision primitives like oriented edge filters, and thus tend to perform better than fully connected networks (although today you’ll likely see a convolutional head on top of a transformer). In natural language processing, transformer models excel at modeling long-range dependencies, and thus tend to perform better than fully connected networks.

So how can we get a good inductive bias for query optimization? Fortunately, researchers in 2016 at Peking University proposed a technique called tree convolution. Originally designed for program language processing, tree convolution is also a great fit for modeling the performance of query plans. Section 4.1 of the Neo paper provides an intuitive overview of tree convolution and how it can be applied to query optimization.

What happened next?

By all measures of an academic project, Neo was a success. I graduated and got a postdoc. The paper has been cited many times, and research on replacing a query optimizer with a deep reinforcement learning agent continues to thrive to this day (for example, check out Roq from IBM). While Neo demonstrated excellent performance, it also revealed (at least to me) two new important facts about query optimization:

-

The tail matters more than the mean. Neo’s RL algorithm seeks to minimize the mean latency of a query plan, and it does so admirably, often matching or even exceeding the performance of expert systems. However, in real systems, tail performance (e.g., the 99th percentile) tends to matter more than the mean latency. Neo would happily increase P99 latency by a few minutes to cut mean latency by a few seconds – a trade that looks great on paper,2 but is often unacceptable in practice.

-

Regressions are killer. Users don’t want their query that was fast today to potentially be slow tomorrow. Reinforcement learning requires exploration to try new ideas, and Neo does exploration the same way that most RL algorithms do: by considering, for each query, a balance between exploiting existing knowledge to try to get the best plan possible, and exploring new ideas to try to get better plans in the future. This is a non-starter for a lot of database engineers who would get paged at 3am when the system decided to explore.

We addressed both these concerns in our follow-up work, Bao, which sat on top of an existing query optimizer instead of wholly replacing one. Bao would later lead to a limited deployment at Microsoft and Meta. In Bao’s industrial adoptions, offline execution was used to ensure that a new candidate plan was evaluated before being deployed, mitigating the risk of regressions. My lab at UPenn has started to explore how to best allocate this offline execution budget, at both the query level and the workload level.

Overall, the future of learned query optimization looks bright. The biggest recent change is, of course, the emergence of LLMs, which have already been integrated into query rewriting systems, steering systems, and RAG-based query optimizers that learn from their mistakes.

Footnotes

-

Video games, and most traditional RL environments, can also be simulated concurrently, potentially running many simulations in parallel on the same machine. In query optimization, the machine itself is part of the “state” – if you run 8 queries in parallel on the same machine, they will interfere with each other, messing up the reward signal. ↩

-

These improvements look good on paper in the sense that plots of the total workload time improve. Obviously, we’ve wisened up since then, and now regularly report tail latency results. ↩